Carshalton Athletic 3 Horsham 1 (Isthmian League Premier Division)

Colston Avenue, 12 October 2020

Colston Avenue, 12 October 2020

Sometimes, football fans tell me they're only interested in the present and not the past, and I never quite believe them. Most people don't spend as much time watching highlights of old games as I do - I'll watch almost anything, going back to the earliest days of film (although the codification of football is more contemporaneous with the development of photography). But every fan wants their club to generate memories: the greatest are the ones that feel best in the moment, winning matches or even trophies, but so much of the game's texture, and emotional appeal, comes from the accumulation of moments that are joyous, sad, funny or infuriating, or even stultifying, and you can learn so much about how supporters relate to it by the recollections that stick with them most.

A melancholic person at heart, who loves that line in Half Man Half Biscuit's Depressed Beyond Tablets about how "all the results of my lifetime are a string of nil-nils", I'm attracted to the disappointing and the dismal, and I find myself talking about Norwich City's lows as much as, if not more than their highs. (Do your own joke about their proportions.) Now enough time has passed, friends and I often look back and laugh at 2008-2009, when Norwich were relegated to the third division for the first time in fifty years after a disastrous season in which they signed seventeen players on loan, meaning that we frequently turned up at matches with no idea who half the squad even were, watching a team that looked like they were having exactly the same experience.

On train trips to games in more recent, better times, we could make each other laugh just by mentioning one of these loanees, almost competing to drag up the most forgotten names. The one that stayed most with me was Omar Koroma, who joined Portsmouth from Gambian club Banjul Hawks in July 2008 and came to Norwich for the 2008-09 season soon after. Manager Glenn Roeder told fans he could sign better players on loan than permanently, calling Koroma "a lovely mover" who was "exciting and full of enthusiasm". I only went to a handful of games that year, but saw one of Koroma's few starts, at Southampton in September 2008, who also went down at the end of the season. It had one of St. Mary's' lowest-ever crowds, but as Southampton were so cash-strapped, barely anyone was on the turnstiles and so I missed the first fifteen minutes, waiting outside in the pouring rain. Koroma was substituted soon after Dejan Stefanović was sent off and David McGoldrick made it 2-0 from a penalty, and he went back to Portsmouth after a serious ankle injury a couple of months later. He never played a Football League match again, trialling with Brøndby and then spending time with Forest Green Rovers, Wealdstone and Dulwich Hamlet, playing in Iceland and Kazakhstan before returning to London and ending up at Carshalton Athletic.

Carshalton were high on my list of clubs to visit this season. This was partly because I thought it would be fun to see Koroma when I'm unable to see the Norwich players with whom I've built up relationships (or the new signings, with whom I would have liked to) and barely know any of those I do see. It was also because Carshalton are the nearest club to Wallington, where my parents grew up - I spent a lot of time around there as a child but haven't been back in a decade, since the last of my grandparents died. I've always liked the way football provides a reason to visit places I otherwise wouldn't, and have seen a lot of England this way - this year, it's London's outermost suburbs and its small satellite towns, and Carshalton sits on the hinterland of those categories.

For some reason, Carshalton often play home matches on Monday nights, making them easy to cross off my list. (There's very little else to do socially besides football right now, after all.) I decided to spend an afternoon wandering around the local area, getting the train to Wallington and walking down the high street for the first time since the mid-1990s. My main memory of it was buying the Playfair Football Annual in WH Smith in 1993: the first time I owned any sort of football directory, feeding my interest in records of the game's recent and longer-term history. I did that with my grandmother, who died in 2012, aged 97; my walk took me past her old house on Croydon Road and to Beddington Park, behind Wallington Grammar School where my dad took his O-Levels. I have a photo of my grandmother at the park in 1928, but no memories of visiting with her: the thing that's stayed with me is my youthful trips to the Science Museum or the Natural History Museum, although it wasn't until this week that I really appreciated how the area was much more an outer district of London than a town in its own right.

My favourite football novel isn't really about football at all (and nor, you might say, are these blogs, most of the time). In his semi-autobiographical work The Unfortunates (1969), famously presented as a set of unbound chapters in a box to be read in any order, B. S. Johnson uses a trip to Nottingham to cover a game as a springboard for a stream of consciousness, thinking about a friend who died of cancer, whom he closely associated with the city. I did the same for my grandmother, remembering childhood afternoons feeding the ducks at Carshalton Ponds, or sat talking under the war memorial, or playing board games and listening to the radio with her in her little kitchen. (For some reason, I have an especially strong memory of listening to Liverpool's FA Cup semi-final against Portsmouth in 1992, in which she had no interest.)

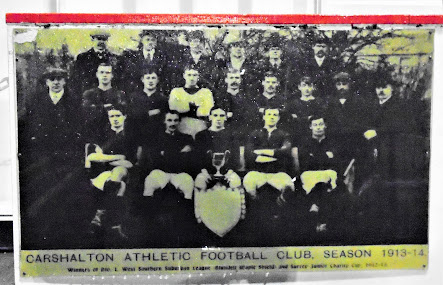

She certainly never mentioned the prospect of going to see Carshalton Athletic with me, any more than my father ever raised the possibility of watching Horley Town, so I didn't have any memories attached to the club. Their ground being on Colston Avenue reminded me of the one political moment I've enjoyed since December: the people of Bristol tearing down the long hated statue of slave trader Edward Colston and throwing into the sea during the Black Lives Matter protests. Carshalton officially call it The War Memorial Sports Ground - people in that part of the country are far keener to remember the world wars than the Empire, for reasons I've explored elsewhere - and on entering, the first thing I saw was a Carshalton Athletic team photo from 1914, the year the First World War started, and my grandmother was born.

Next, I looked out for Omar Koroma, the only current Carshalton player I knew. Luckily he was starting. On my way, I thought back to 90 Minutes, my favourite football magazine as a teen, and their 'My Sad Mate' feature - another stupid thing that had stayed with me, especially the Bristol Rovers fan who had gone to QPR to see striker Devon White, who had recently left for Loftus Road, only to find that White wasn't playing. It took him some time to get into the game, but gradually he became the focal point of the Robins' attack, and I found out that he'd already scored four goals this season. He came alive in the second half, with his team already 2-0 up as Horsham managed to score two virtually identical own goals from Carshalton corners. I had my camera ready as Koroma broke through on goal and clattered into Horsham's keeper; I was just about to text a snide comment to my friend Chris when Koroma struck a low shot underneath the goalkeeper after a lovely Carshalton move.

A few Norwich fans on Twitter were delighted that I'd seen Koroma score; the Carshalton supporters around me were annoyed that he was substituted soon after. Writing this, I looked up the report from that last time I'd watched him, and saw I'd remembered it wrong: Koroma, just 18 years old, had a lively match and made a few chances, enough so that he'd started Norwich's next match, at home to Derby County. Perhaps he impressed less: Norwich lost 2-1 with Koroma on the wing for an hour, before he was taken off and not seen again. (The game was later part of an investigation into match-fixing.) So perhaps I owed Koroma an apology, and probably my father as well: I used to make fun of him for talking in Cockney rhyming slang, thinking Wallington and Carshalton were firmly in Surrey, but on returning, they felt far more like Greater London, as Ian Nairn pointed out in his reflections on nearby Mitcham in his book on the county. Leaving the ground and seeing the 1913-14 photo again, I thought about how football is about generating memories, whether they be converted into terrace chants, nostalgic pub chats or pieces of writing; either way, that connection with its numerous, endless narratives is what keeps me coming back.